You’ve probably heard of a stock exchange before. After all, it’s your supermarket for stocks and ETFs. But do you know how exchanges work? In this entry, you’ll learn how markets clear, what’s the bid and the ask price, what’s liquidity, and what type of order you should use when.

From financial markets to exchanges

We’ll start from the big picture. Exchanges serve financial markets, so let’s first focus on what are financial markets. There’s more than green & red numbers on a computer screen.

What are financial markets?

Financial markets are any marketplace where trading takes place [1]. What is it that you trade? Can be anything. Commodities, forex, real estate, or securities are typical examples. For our purposes, let’s focus on securities.

What are securities?

A security is a financial instrument that has value [2]. You can trade securities with others in return for cash or other securities. Security sounds like a very abstract term, but in reality is not. Let’s look at some tangible examples of securities. We can categorize them in three buckets [3]:

- Debt: government bonds, corporate bonds etc.

- Equity: stocks, equity ETFs etc.

- Derivatives: options, futures, swaps etc.

It doesn’t matter if you don’t understand all terms above. For our practical purposes as long term investors, securities = bonds & stocks. ETFs behave like stocks, so they’re part of the equation as well.

How do you trade securities?

Broadly speaking, securities can trade in two different ways: over-the-counter (OTC) or on an exchange.

OTC trading is done directly between two parties [4, 5]. You don’t like OTC trading. Why? First, because it’s cumbersome. You have to go after multiple dealers to find what you want. And second, because it’s not very transparent. Prices of previous transactions are not necessarily made public. As a result, you never know if you’re trading at a fair price. The bond market is an example of OTC trading. For clarity, you may also picture the market for second-hand cars through car dealers. It hopefully illustrates more clearly the cumbersomeness and lack of transparency I was referring to.

Trading on an exchange is different. An exchange is an organized market that ensures fair and orderly trading [6, 7]. In an exchange, trading is centralized. You don’t trade individually with a counterpart anymore. Instead, you submit orders to the exchange. The exchange then matches your orders with orders from other participants. If opposite-side orders match, markets clear. But more on market clearing in a second. For now, remember that you like exchanges. Exchanges are cool. They make it easy to trade. And bring transparency. Any trade that takes place on an exchange is public information. That means that you can check current or previous prices at which a security has traded. The stock market is an example of exchange trading.

How do you get orders to an exchange?

You don’t interact with exchanges yourself. Instead, you trade through a broker. Brokers take your orders to an exchange.

A broker isn’t a dealer. The main difference is dealers hold securities themselves. Brokers don’t. Brokers simply take your orders to the exchange and exchange your money for securities or vice-versa if your order is filled. They own nothing.

How markets clear on an exchange

One of the key characteristics of an exchange is centralized market clearing. What does that mean? How does it work?

What does it mean for markets to clear

Markets clear whenever a transaction between a buyer and a seller occurs. The way this happens is one of the cornerstones of free markets and capitalism. And affects you whenever you trade a security.

A simple fictitious market

Imagine a simple, fictitious market. All you can do in this market is buy and sell apples. And all trades take place on an exchange.

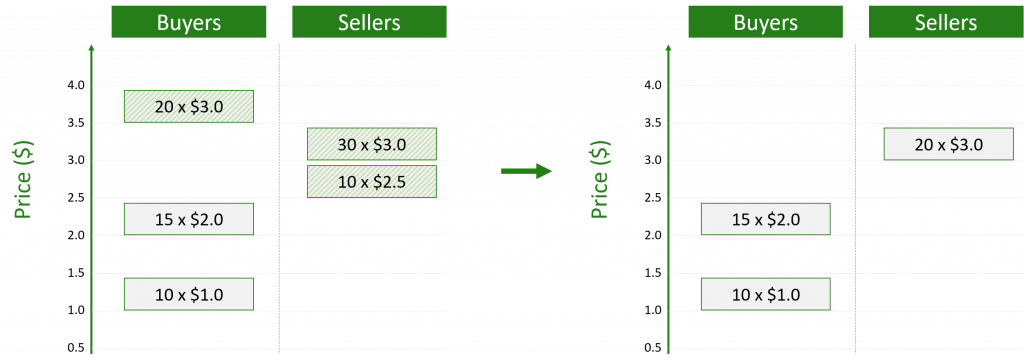

There are initially two buyers and two sellers in the market. The first buyer is willing to buy 15 apples at a price of $2 each (note: these are Swiss apples). The second buyer is willing to buy 10 apples at a price of $1. Similarly, the first seller is willing to sell 10 apples at a price of $2.5. The second 30 apples at a price of $3. We can represent the market visually like this:

A market in equilibrium

Alright, so what happens next? Nothing. The lowest price at which a seller is willing to sell is $2.5. And the highest price at which a buyer is willing to buy is $2. The market won’t clear. It’s in equilibrium already.

In market terms, the lowest price at which a seller is willing to sell is called the ask price. And the highest price at which a buyer is willing to buy is called the bid price.

The ask price of our market is $2.5. And the bid price is $2.0. They don’t overlap, so nothing happens. The bid price has to be greater or equal than the ask price for markets to clear.

Market clearing

A new buyer comes to the market. Let’s call her Sara. Sara just got a fat bonus and is feeling euphoric. She’s willing to buy 20 apples at a price of $3.5. She submits an order to the exchange accordingly.

What happens next? Well, the bid price is now $3.5. And the ask price is $2.5. Bid is greater than ask. The markets will clear.

How will markets clear? First, 10 apples will transact at a price of $2.5 between Sara and the first seller. This trade will exhaust the supply from the first seller. But Sara is still buying 10 additional apples. Because the second seller is willing to sell at a price that is still below the bid price, markets will clear again. Another 10 apples will change hands at a price of $3 between Sara and the second seller. At this point, there’s no demand for more apples. So the second seller is left with 20 apples.

Although it took a while to describe, in electronic exchanges the whole process actually happens nanoseconds after Sara submits the order.

All in all, Sara bought 20 apples for a total price of $55. That’s on average $2.75 per apple. Which is great, because she was willing to pay up to $3.5. The sellers are also happy, because they sold at the price they were willing to sell.

Market clearing in real life

Reality is very similar to our fictitious market for apples. Only that there’s not a single product to transact. There’s millions. Oil, Microsoft shares, an S&P 500 ETF, silver, a bond ETF, Toyota shares, you name it.

In reality, there’s also not just 4 or 5 market participants. At least not for liquid products. There might be millions of market participants for popular securities (e.g. Microsoft shares). Markets might clear thousands of times per minute. And each transaction might have an average volume of hundreds or thousands of shares.

The market price

We’ve seen that there’s two prices that jointly govern market transactions. The bid and the ask. Markets clear when bid is greater or equal than ask. But we often hear things like the price of Tesla is $420. How come they quote a single price? Is this the bid? Or is it the ask? Is it the average of the two? It’s neither. The market price is the last traded price for a given security.

The market price is not necessarily a fair price. A better candidate for a fair price is the mid-point between bid and ask.

The info we see on an exchange

You’re now ready to look at a real example. Let’s look at all the info we see on an exchange when we select a security. Which security should we use as an example? Well, Apple.

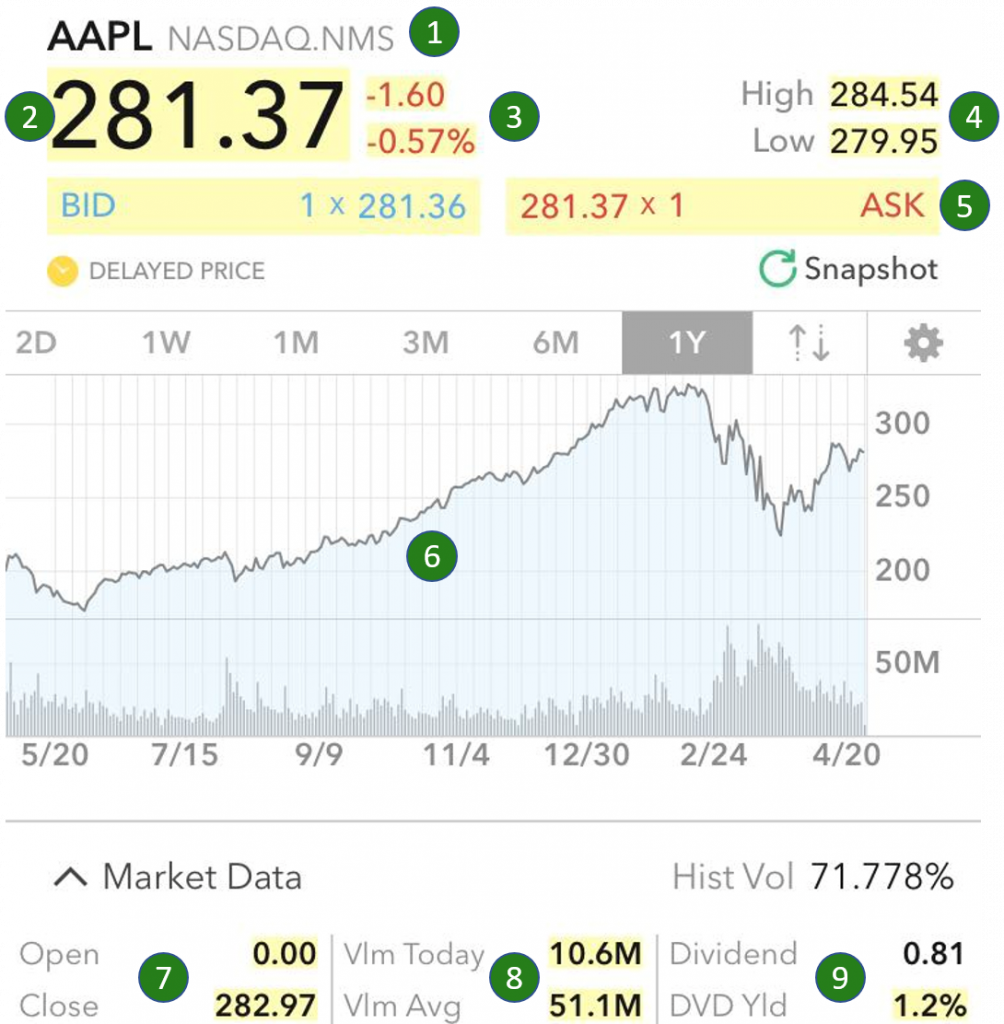

- The ticker of the security and the exchange. The ticker is kind of a short nickname. Apple trades on the Nasdaq Stock Exchange in New York City. Nasdaq opens at 9:30 and closes at 16:00 EST

- The market price. We just saw that this is the last price at which Apple traded

- Price variations since the opening. Top part displays absolute units (USD in this case). Bottom part relative change

- Intra-day highest and lowest transaction prices

- Bid and ask. Interestingly, the volume for either is just one share at this particular time

- Historical price chart

- Open and close of the last trading session. Open shouldn’t be 0, it’s likely a glitch

- Volume is the number of shares traded. Top part indicates today. Bottom part average. The time period for the average is not specified, though

- Dividend and dividend yield for the stock

Remember that what you do not see is the queue or orders that are less competitive than the bid or the ask. We used those for illustration in our fictitious market. In reality you only see bid and ask.

Market liquidity

The more participants in a market, the more liquid the market is. Liquidity is the ease with which you can convert an asset to cash [8]. It might seem like it’s one of those market properties that is just good to to know about. But it’s more than that. Liquidity affects you a great deal. The liquidity of your portfolio is as important as its volatility.

Measuring liquidity: the bid-ask spread

Our market for apples was extremely illiquid. After all there were only 5 participants. Trading becomes more efficient in a market with thousands or millions of participants. There’s so many orders out there that we won’t see big price gaps between what sellers demand and what buyers are willing to offer. As a result, bid and ask prices will be closer.

The difference between bid and ask is called bid-ask spread. The bid-ask spread is a measure of market liquidity. The narrower the bid-ask spread, the more liquid the market. You want a small bid-ask spread, because it allows you to trade at prices closer to the market fair price (the mid-point between bid and ask).

To illustrate the benefits of a narrow bid-ask spread, let’s think of the opposite case. Think of a market with very big bid-ask spreads. You know one already. The market for houses. The real estate market. Real estate is not that different from our fictitious market for apples. There are few buyers and few sellers for a given asset. You might want to sell your house for $300k. But the only two buyers interested are willing to pay $250k and $260k, respectively. The bid-ask spread is huge. It might take you months to sell a house at a price you’re willing to. You don’t like that.

Trades move the price easily in illiquid markets

Let’s go back to our market for apples. Remember how Sara broke into the market willing to buy at $3.5? Based on the bid and ask prices before Sara’s trade, the previous market price was likely between $2 and $2.5. After Sara’s purchase, the price increased to $3. Sara moved the price of apples.

Besides, Sara’s actions might have long term consequences. Sellers were happy at the time because they managed to sell their products at the price they wanted. Going forward, however, sellers might change their strategy. Especially the first seller, who run out of stock, might wonder whether he could have sold his 10 apples for more money. After all, it seems like buyers are willing to pay more.

Think about it. If the ask price changes in response to Sara’s trade, a single buyer has moved the price. The lesson learned is that, in illiquid markets, few transactions can affect the market price a great deal.

Benefits of liquidity

You should see by now that you like liquidity. You want your portfolio to be liquid. Let’s gather all advantages of liquidity. In general, higher liquidity means that:

- It’s easier to convert assets to cash: in a liquid market there are countless trades per day. We saw that, on average, more than 50 million Apple shares change hands in a given day. At current prices, that’s over $15 billion changing hands every day. Just in Apple stock. In such environment, it’s extremely easy to convert securities to cash, and vice-versa. And trading won’t move the price against you. We shouldn’t take this for granted. We saw the potential pains of converting an asset to cash in an illiquid market, such as real estate.

- Bid-ask spreads are small: liquid securities are traded by countless different market participants. As you throw more and more players to an exchange, the chances that any of them is willing to trade at a given price increase. This results in bid-ask spreads getting narrower and narrower the more liquid a market is. And a narrow bid-ask spread helps you buy the security at the best possible price

- There’s transparency around the fair price of an security: we saw that the market price is the last traded price. For liquid markets, this is very representative of the fair price of a security. Why? Because there are hundreds or thousands of trades per minute. The price of the security is being constantly updated based on supply and demand. Any news will trigger a reaction in the bid and asks prices. What are news? It could be anything. For example, geopolitical events, a tweet, a press release from a competitor, a press release from the company itself etc.

Types of orders

We saw that exchanges are a type of financial market in which trading is centralized. To trade on an exchange, you don’t talk to other market participants. Instead, you submit orders to the exchange. What type of orders can you submit? Broadly speaking, two: limit orders and market orders.

Limit orders

Limit orders are a type of order to indicate that you’re only willing to trade at a specific price or better [9]. Better price is of course relative. If you’re a buyer and submit a limit order to buy 10 shares of Amazon at $2,000 per share, the order will only get filled at $2,000 or lower. If you submit a limit order to sell the same stock at the same price, it’ll get filled at $2,000 or higher.

Limit orders are easy to understand. Our fictitious market for apples was based solely on limit orders. Everyone had formed an opinion about the price at which they were willing to transact.

With a limit order, the price is guaranteed. But the filling is not. The price of the security might never reach your desired price. And hence you might never trade. In our market for apples, the poor soul who submitted a buy order for 10 apples at $1 might never get them. Not unless he changes the price of the limit order. These are Swiss apples after all.

Market orders

Market orders are orders with which you request to trade at the best available price [10]. With market orders, you don’t specify a target price. Instead, you take the best ones already available. With a market order, the filling is guaranteed. But the price is not.

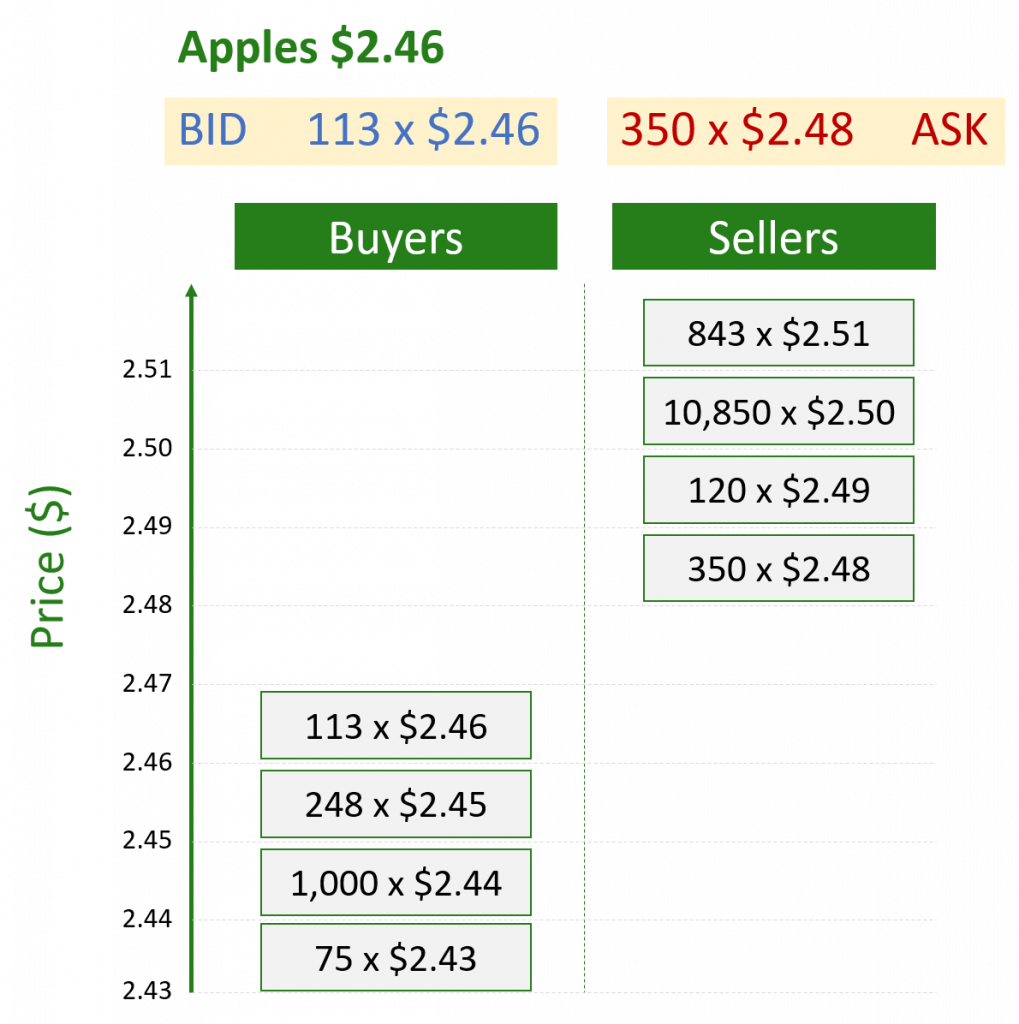

We didn’t cover market orders in our fictitious market for apples. So let’s circle back and see how it’d work. By the way, some exciting news. The market for apples became very liquid in the meantime. There’s now hundreds of participants. Just look at the bid-ask spread and the distribution of orders.

What happens if we submit a market order to buy 500 apples? We’ll get 350 at $2.48, 120 at $2.49 and 30 at $2.50. Our average purchase price is $2.4836.

And what happens if we submit a market order to sell 75 apples? We’ll sell them all at $2.46.

Which order type should I use?

If you trade liquid securities when markets are open, you should feel comfortable using market orders. Why? Because the trading of liquid securities is efficient enough for you to get a fair price no matter what. Retail investors (you) are small enough not to move the price, whatever you do. So which securities can be considered liquid? The shares of any company you can name are liquid. Any fund listed here is liquid.

If instead you submit limit orders, implicitly you’re anticipating that you can get a better price than what’s currently available. On what grounds do you believe that? Are you timing the market? We learned here that you shouldn’t…

Some brokers (e.g. Interactive Brokers) allow to submit a mid-price order. These enhanced algorithms allow you to split the difference between bid and ask with another market participant who’s also submitting a mid-price order in the opposite direction. Always go for such options if available.

A reflection on financial markets

You now understand how financial markets work from an operational perspective. But it’s important not to lose the big picture. The way financial markets are structured is one of the cornerstones of capitalism. Why? Because:

- Resources are allocated optimally: it’s always the buyer who’s willing to pay the most the one that gets to buy. In theory, the buyer who’s willing to pay the most is the one that will extract the most value from the purchase

- Supply and demand create the right incentives: bid and ask are influenced by the market forces of supply and demand. When there’s a lot of demand, the bid tends to go up. This creates the right incentives for sellers to produce more. Or for alternative products to step up

- Trading creates transparency: exchanges disseminate information about the perceived fair price of a security. Perceived by whom? By the common wisdom of all market participants. This results in transparency. A transparent game is usually a fair game

This is not to blindly advocate for free markets. They’re not perfect. Monopolies and externalities are examples of market failures. But it’s still very interesting to think of the socioeconomic consequences of something as simple as free market clearing.

What you’ve learnt

Great job! You now have an understanding of how financial markets work. Especially when you trade on an exchange, which is the most relevant type of trading for a retail investor. In this entry, you’ve learnt:

- What’s a financial market

- What’s a security

- The two main ways to trade: OTC and on an exchange

- The benefits of trading through an exchange

- What’s the bid price and the ask price

- How markets clear

- What’s liquidity and how it affects you

- What’s the bid-ask spread and what it tells you

- The difference between a limit order and a market order

Last updated on April 21, 2021

8 replies on “Exchanges, liquidity and order types”

Very helpful for the first time investors!

Love your blog. Very high quality information presented in an easy-to-understand way.

I think I found a small typo. Shouldn’t the price be $2.43 in this example?

“And what happens if we submit a market order to sell 75 apples? We sell them all at $2.46. “

Thank you aarhorn for you kind words! 🙂

In the example you mention, the bid is 113 x $2.46. That means there’s a buyer willing to buy 113 apples at a price of $2.46. If we submit a market order to sell 75, this buyer (let’s call it buyer A) will get them all.

Buyer A has “priority” over the buyer who’s willing to buy 75 apples at a price of $2.43 per apple (buyer B) because buyer A is willing to pay more. The fact that the quantities match (we’re selling 75 while buyer B is willing to buy exactly 75) is not as important as the bid price. The bid price is the one actually determining the “priority in the buying queue”: the higher the bid price, the higher the priority. Does that make sense?

Thanks. It makes sense. The seller wants to get the highest price.

AverageBoy, your blog is fantastically well-written. Nice job, and thank you!

You wrote “Some brokers (e.g. Interactive Brokers) allow to submit a mid-price order. These enhanced algorithms allow you to split the difference between bid and ask with another market participant who’s also submitting a mid-price order in the opposite direction. Always go for such options if available” … which surprised me as I had never come across the term “mid-price order”.

Could you please explain it a bit more in layman’s terms, or perhaps point me toward another resource? In the various forums that I read, my impression is that very few people are using this order type. Thanks!

Hi Schuyler and thanks for the kind words! 🙂

Mid-price orders aren’t a theoretical order type per se, but rather the branding name IB gave to its “smart orders”. These are supposed to be more efficient than traditional order types. IMO it always makes sense to buy this way through IB. Further reading here and here.

PS. Your nickname reminds me of this

Hi. Great, clear explanations!

Is this correct? Or is the ask price $2.5? I might be missing something.

“What happens next? Well, the bid price is now $3.5. And the ask price is $3. Bid is greater than ask. The markets will clear.”

It was a mistake and the ask price should indeed be $2.5. I updated the post. Thanks for your contribution!!